172x Filetype PDF File size 0.16 MB Source: users.exa.unicen.edu.ar

1. Concept: Agile Practices and RUP

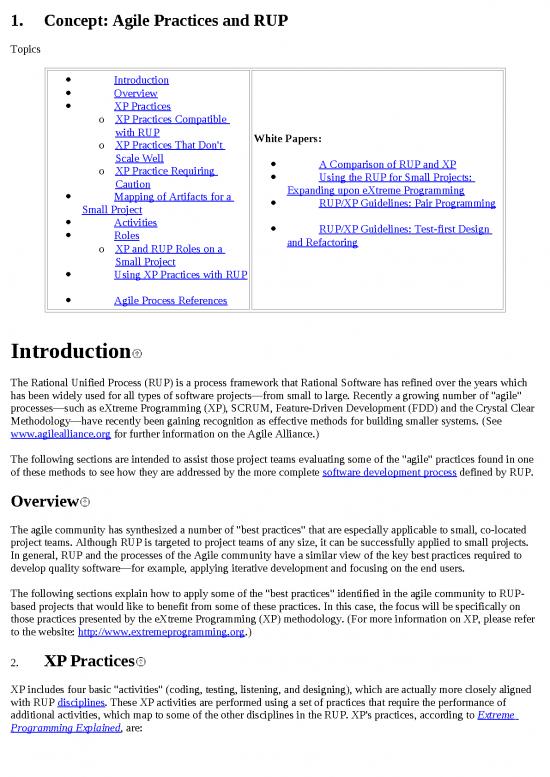

Topics

Introduction

Overview

XP Practices

o XP Practices Compatible

with RUP White Papers:

o XP Practices That Don't

Scale Well A Comparison of RUP and XP

o XP Practice Requiring Using the RUP for Small Projects:

Caution Expanding upon eXtreme Programming

Mapping of Artifacts for a RUP/XP Guidelines: Pair Programming

Small Project

Activities RUP/XP Guidelines: Test-first Design

Roles and Refactoring

o XP and RUP Roles on a

Small Project

Using XP Practices with RUP

Agile Process References

Introduction

The Rational Unified Process (RUP) is a process framework that Rational Software has refined over the years which

has been widely used for all types of software projects—from small to large. Recently a growing number of "agile"

processes—such as eXtreme Programming (XP), SCRUM, Feature-Driven Development (FDD) and the Crystal Clear

Methodology—have recently been gaining recognition as effective methods for building smaller systems. (See

www.agilealliance.org for further information on the Agile Alliance.)

The following sections are intended to assist those project teams evaluating some of the "agile" practices found in one

of these methods to see how they are addressed by the more complete software development process defined by RUP.

Overview

The agile community has synthesized a number of "best practices" that are especially applicable to small, co-located

project teams. Although RUP is targeted to project teams of any size, it can be successfully applied to small projects.

In general, RUP and the processes of the Agile community have a similar view of the key best practices required to

develop quality software—for example, applying iterative development and focusing on the end users.

The following sections explain how to apply some of the "best practices" identified in the agile community to RUP-

based projects that would like to benefit from some of these practices. In this case, the focus will be specifically on

those practices presented by the eXtreme Programming (XP) methodology. (For more information on XP, please refer

to the website: http://www.extremeprogramming.org.)

2. XP Practices

XP includes four basic "activities" (coding, testing, listening, and designing), which are actually more closely aligned

with RUP disciplines. These XP activities are performed using a set of practices that require the performance of

additional activities, which map to some of the other disciplines in the RUP. XP's practices, according to Extreme

Programming Explained, are:

The planning game: Quickly determine the scope of the next release by combining business priorities

and technical estimates. As reality overtakes the plan, update the plan.

Small releases: Put a simple system into production quickly, then release new versions on a very short

cycle.

Metaphor: Guide all development with a simple shared story of how the whole system works.

Simple design: The system should be designed as simply as possible at any given moment. Extra

complexity is removed as soon as it is discovered.

Testing: Programmers continually write unit tests, which must run flawlessly for development to

continue. Customers write tests demonstrating that features are finished.

Refactoring: Programmers restructure the system without changing its behavior to remove duplication,

improve communication, simplify, or add flexibility.

Pair programming: All production code is written with two programmers at one machine.

Collective ownership: Anyone can change any code anywhere in the system at any time.

Continuous integration: Integrate and build the system many times a day, every time a task is

completed.

40-hour week: Work no more than 40 hours a week as a rule. Never work overtime a second week in a

row.

On-site customer: Include a real, live user on the team, available full-time to answer questions.

Coding standards: Programmers write all code in accordance with rules emphasizing communication

through the code.

Activities performed as a result of the "planning game" practice, for example, will mainly map to the RUP's project

management discipline. But some RUP topics, such as business modeling and the deployment of the released software,

are outside the scope of XP. Requirements elicitation is largely outside the scope of XP, since the customer defines

and provides the requirements. Also, because of simpler development projects it addresses, XP can deal very lightly

with the issues the RUP covers in detail in the configuration and change management discipline and the environment

discipline.

XP Practices Compatible with RUP

In the disciplines in which XP and the RUP overlap, the following practices described in XP could be—and in some

cases already are—employed in the RUP:

The planning game: The XP guideance on planning could be used to achieve many of the objectives

shown in the Project Management discipline of RUP for a very small project. This is especially useful for low-

formality projects that are not required to produce formal intermediate project management artifacts.

Test-first design and refactoring: These are good techniques that can be applied in the RUP's

implementation discipline. XP's testing practice, which requires test-first design, is in particular an excellent

way to clarify requirements at a detailed level. As we'll see in the next section, refactoring may not scale well

for larger systems.

Continuous integration: The RUP supports this practice through builds at the subsystem and system

levels (within an iteration). Unit-tested components are integrated and tested in the emerging system context.

On-site customer: Many of the RUP's activities would benefit greatly from having a customer on-site

as a team member, which can reduce the number of intermediate deliverables needed—particularly documents.

As its preferred medium of customer-developer communication, XP stresses conversation, which relies on

continuity and familiarity to succeed; however, when a system—even a small one—has to be transitioned,

more than conversation will be needed. XP allows for this as something of an afterthought with, for example,

design documents at the end of a project. While it doesn't prohibit producing documents or other artifacts, XP

says you should produce only those you really need. The RUP agrees, but it goes on to describe what you

might need when continuity and familiarity are not ideal.

Coding standards: The RUP has an artifact—programming guidelines—that would almost always be

regarded as mandatory. (Most project risk profiles, being a major driver of tailoring, would make it so.)

Forty-hour week: As in XP, the RUP suggests that working overtime should not be a chronic

condition. XP does not suggest a hard 40-hour limit, recognizing different tolerances for work time. Software

engineers are notorious for working long hours without extra reward—just for the satisfaction of seeing

something completed—and managers need not necessarily put an arbitrary stop to that. What managers should

never do is exploit this practice or impose it. They should always be collecting metrics on hours actually

worked, even if uncompensated. If the log of hours worked by anyone seems high over an extended period, this

certainly should be investigated; however, these are issues to be resolved in the circumstances in which they

arise, between the manager and the individual, recognizing any concerns the rest of the team might have. Forty

hours is only a guide—but a strong one.

Pair programming: XP claims that pair programming is beneficial to code quality, and that once this

skill is acquired it becomes more enjoyable. The RUP doesn't describe the mechanics of code production at

such a fine-grained level, although it would certainly be possible to use pair programming in a RUP-based

process. Some information on pair programming—as well as test-first design and refactoring—is now provided

with the RUP, in the form of white papers. Obviously, it is not a requirement to use any of these practices in

the RUP, however in a team environment, with a culture of open communication, we would hazard a guess that

the benefits of pair programming (in terms of effect on total lifecycle costs) would be hard to discern. People

will come together to discuss and solve problems quite naturally in a team that's working well, without being

obliged to do so.

The suggestion that good process has to be enforced at the "micro" level is often unpalatable and may not fit some

corporate cultures. Strict enforcement, therefore, is not advocated by RUP. However, in some circumstances, working

in pairs—and some of the other team-based practices advocated by XP—is obviously advantageous, as each team

member can help the other along; for example:

in the early days of team formation, as people are getting acquainted,

in teams inexperienced in some new technology,

in teams with a mix of experienced staff and novices.

XP Practices That Don't Scale Well

The following XP practices don't scale well for larger systems (nor does XP claim they do), so we would make their

use subject to this proviso in the RUP.

Metaphor: For larger, complex systems, architecture as metaphor is simply not enough. The RUP

provides a much richer description framework for architecture that isn't just—as Extreme Programming

Explained describes it—"big boxes and connections." Even in the XP community, metaphor has more recently

been deprecated. It is no longer one of the practices in XP (until they can figure out how to describe it well—

maybe a metaphor would help them).

Collective Ownership: It's useful if the members of a team responsible for a small system or a

subsystem are familiar with all of its code. But whether you want to have all team members equally

empowered to make changes anywhere should depend on the complexity of the code. It will often be faster

(and safer) to have a fix made by the individual (or pair) currently working on the relevant code segment.

Familiarity with even the best-written code, particularly if it's algorithmically complex, diminishes rapidly over

time.

Refactoring: In a large system, frequent refactoring is no substitute for a lack of architecture. Extreme

Programming Explained says, "XP's design strategy resembles a hill-climbing algorithm. You get a simple

design, then you make it a little more complex, then a little simpler, then a little more complex. The problem

with hill-climbing algorithms is reaching local optima, where no small change can improve the situation, but a

large change could." In the RUP, architecture provides the view and access to the "big hill," to make a large,

complex system tractable.

Small Releases: The rate at which a customer can accept and deploy new releases will depend on many

factors, typically including the size of the system, which is usually correlated with business impact. A two-

month cycle may be far too short for some types of system; the logistics of deployment may prohibit it.

XP Practice Requiring Caution

Finally, an XP practice that at first glance sounds potentially usable in the RUP—Simple Design—needs some

elaboration and caution when applied generally.

Simple Design

XP is very much functionality driven: user stories are selected, decomposed into tasks, and then implemented.

According to Extreme Programming Explained, the right design for the software at any given time is the one

that runs all the tests, has no duplicated logic, states every intention important to the programmers, and has the

fewest possible classes and methods. XP doesn't believe in adding anything that isn't needed to deliver business

value to the customer.

There's a problem here, akin to the problem of local optimizations, in dealing with what the RUP calls

"nonfunctional" requirements. These requirements also deliver business value to the customer, but they're more

difficult to express as stories. Some of what XP calls constraints fall into this category. The RUP doesn't

advocate designing for more than is required in any kind of speculative way, either, but it does advocate

designing with an architectural model in mind-that model being one of the keys to meeting nonfunctional

requirements.

So, the RUP agrees with XP that the "simple design" should include running all the tests, but with the rider that

this includes tests that demonstrate that the software will meet the nonfunctional requirements. Again, this only

looms as a major issue as system size and complexity increase, or when the architecture is unprecedented or the

nonfunctional requirements onerous. For example, the need for marshalling data (to operate in a heterogeneous

distributed environment) seems to make code overly complex, but it will still be required throughout the

program.

3. Mapping of Artifacts for a Small Project

When we tailor the RUP for a small project and reduce the artifact requirements accordingly, how does this compare to

the equivalent of artifacts in an XP project? Looking at the example development case for small projects in the RUP,

we see a sample RUP configuration has been configured to produce fewer artifacts (as shown in Table 1).

RUP Artifacts

XP Artifacts (from Example Development Case for Small

Projects)

Stories Vision

Additional documentation from conversations Glossary

Use-Case Model

Constraints Supplementary Specifications

Test Plan

Acceptance tests and unit tests Test Case

Test data and test results Test Suite (including Test Script, Test Data)

Test Log

Test Evaluation Summary

Software (code) Implementation Model

Releases Product (Deployment Unit)

Release Notes

Metaphor Software Architecture Document

Design (CRC, UML sketch)

Technical tasks and other tasks Design Model

Design documents produced at end

Supporting documentation

Coding standards Project Specific Guidelines

Workspace Development Case

Testing framework and tools Test Environment Configuration

Release plan Software Development Plan

Iteration plan Iteration Plan

Story estimates and task estimates

Overall plan and budget Business Case

Risk List

Reports on progress Status Assessment

Time records for task work Iteration Assessment

Metrics data (including resources, scope, Review Record

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.